Michigan Central Innovation District Has Made Great Strides Since June 2018 Announcement

August 19, 2021

In June 2018, at an event that featured the Detroit Children’s Choir alongside community leaders and activists, Ford made headlines around the world with the announcement that the company had acquired Detroit’s iconic Michigan Central Station. Designed by the same architects as New York’s Grand Central, the building had become a prime example of vacant Detroit real estate during decades of disuse, but the company announced the beginning of a new era for the building: Michigan Central Station would be lovingly restored as the centerpiece of an innovation hub focused on designing the mobility solutions of the future: autonomous vehicles, electric vehicles, scooters, light rail, drones, and beyond.

In the three years since, despite a global pandemic, vision for that innovation district has only sharpened and grown, with new plans to welcome innovators from around the globe to design and prototype in one of the nation’s most important historical restoration projects, with deep roots in, and deep commitment to, the Detroit community.

“We want this to be a community space,” Bill Ford, Executive Chair of Ford Motor Company, declared in the original announcement. “We want everyone to be involved.” Over the past three years, the company has put this promise into action. As plans for the restoration came together, Ford laid groundwork of another kind in the community, creating a Community Benefits Agreement with Detroit that contained over forty commitments to affordable housing, workforce development, youth development and education, and neighborhood development, including grants for everything from community art projects to home repair. And Michigan Central has worked to create an ongoing dialogue with the local community, through a newsletter published in both English and Spanish, a local information center, and regular community meetings.

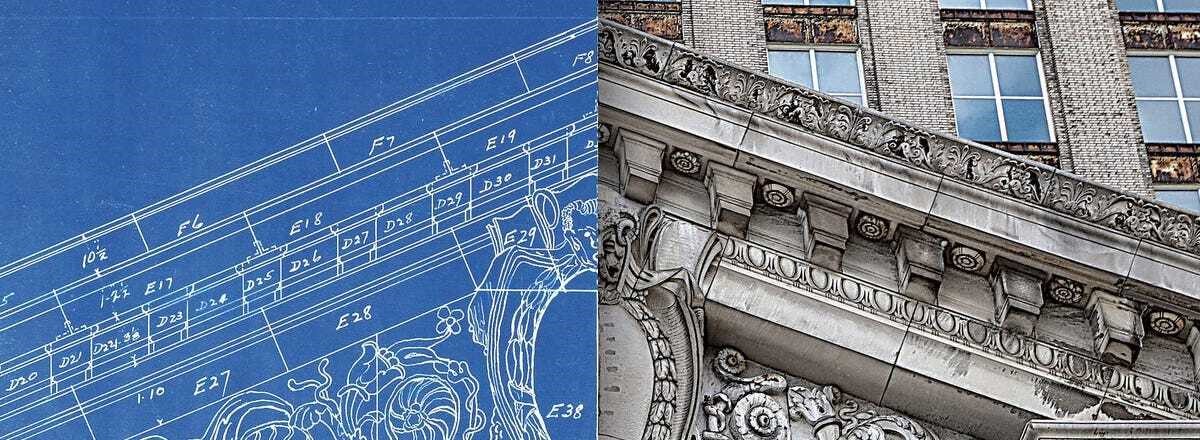

At the same time, architects and builders are making progress on a restoration that they say is both important and unique. Quinn Evans, the architect of record for Michigan Central Station, has restored the Lincoln Memorial, Mount Vernon, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water, but Richard Hess, who leads the Michigan Central Station restoration from their Detroit office, says that this job “takes every skill set and level of expertise in restoration,” from plaster to terracotta, and from to stone to steel.

Detroit firm The Christman Company, in a joint venture with L.S. Brinker, is serving as Construction Manager for the project. Christman/Brinker’s experience includes construction of the Masonic Temple and the Fisher Building, and restorations on the Michigan State Capitol, the U.S. Capitol, and Ernest Hemingway’s Cuban home. But Ron Staley, who leads their team at Michigan Central Station, says that Ford “really set the standard” in their commitment to a beautiful restoration, from the smallest details, like putting someone on a plane to find a decorative element in another state, to adjusting plans when a 60,000 square foot sub-basement, not noted in any of the existing plans, was discovered after millions of gallons of water were pumped out of the main basement. Hess has also been impressed by Ford’s “persistence and determination.” Many restorations, even smaller ones, have timelines of six or eight years. But on Ford’s schedule, Michigan Central will be done in less than five, with the majority of construction scheduled for completion at the end of 2022.

Before the sale of the building, the first question planners had to answer was whether the structure could even be salvaged. “We’d never seen anything of this size in this form of abandonment,” says Staley. Due to roof damage, rain had been pouring into the building for years, leaving about five feet of standing water in the basement, and six feet of ice that collected each winter on top of the striking Guastavino tile domes in the main atrium. The building had also stood without windows for at least a decade.

In the dead of winter, when entire hallways were full of snowfall and ice, architects and engineers walked and sometimes crawled through the building to complete an initial inspection. The news was good: despite the challenges, the bones of the building were still strong. But the restoration effort had started just in the nick of time. If it had stood empty for a few more years, both Staley and Hess say, it might have reached a point of no return.

Starting the project was daunting, because of its historical importance, its meaning in the Detroit community, and its sheer size. “There’s no other Mount Vernon in the country,” says Hess. “There’s no other Lincoln Memorial. And there’s no other Michigan Central. It is one of a kind.” But Richard Bardelli, who spearheads construction for Ford, estimated what it would take to rebuild it by breaking the massive project down into parts: office building, hotel, parking deck. And architects at Quinn Evans drew plans to fix it, Hess says, “the same way we fix anything: brick by brick.”

Job number one was safety. The building didn’t come anywhere near to meeting OSHA standards: floors were full of holes, tile and terracotta were in danger of falling from the ceiling and roof, staircases had no handrails, and none of the building’s original electric systems were capable of providing power. Rooms were also full of debris, some of it hazardous. Before architects and engineers could walk in, Christman/Brinker’s team had to make it safe.

Once workers arrived, the major task was dealing with water: pumping millions of gallons out of the basement, making sure no more could get in, and letting plaster and stone that had absorbed moisture dry out so they could work with it, which took the better part of a year. After stabilization, workers began restoration on the rest of the building, putting in the underlying mechanical systems. One major challenge: installing ductwork for modern heating and cooling, since the “air-conditioning” of 1913, when the building was designed, consisted of opening the giant windows on the face of the building to let in a breeze.

Today, at the third anniversary of the original announcement, the team has entered the third and final phase of construction: creating the finishes that will make the building seem new again, including a massive concrete pour in the basement to anchor the foundation, cleaning the Guastavino tiles in the main waiting room, restoring plaster, and rebuilding lost elements, like the gigantic waiting room chandeliers, based on original plans and old photographs. New glass will be fitted into the striking arches of the ground-floor facade this summer, a highly-visible and moving milestone for the building, after decades of standing open to the elements.

The whole restoration process has blended respect for the past with modern technology, just as the Michigan Central innovation district will when construction is complete. Plasterers repair walls with techniques similar to builders from a hundred years before, while other workers instal elements created by cutting-edge, Ford-designed 3-D modeling–to look just like the originals.

The work won’t just restore the building to what some residents remember, Staley says, because even before it closed in 1988, the station had already become run down, with stains and peeling paint. He thinks many will be astonished by the beauty of the finished restoration: “Nobody in our lifetime has ever seen the building look this way.”

But the Michigan Central Innovation district isn’t just about restoring Detroit’s architectural treasures. It’s firmly focused on driving the future of mobility for the entire world, and innovators are already coming together to create an ecosystem of innovation on the streets around the station. As originally planned, Ford’s autonomous and electric vehicle teams have moved to the neighborhood, and this summer innovators from across the country will begin piloting projects at Michigan Central. Curated by Newlab, which created a world-class innovation hub in Brooklyn, Michigan Central’s first pilots were created in response to the needs of local residents, and include everything from a navigation app for blind people, to autonomous delivery, to solar power signs.

When it’s complete, Michigan Central will be the world’s most ambitious innovation district, and its most all-encompassing, the only one to welcome all forms of mobility, from cars to drones, along with supporting technologies like cutting-edge energy. And it will be part of a unique ecosystem, welcoming innovators, community members, and guests with green spaces, local retail and restaurants, programs and events, and art and culture.

Michigan Central hopes that deep connection with the community might help make mobility in the future more equitable, as well. New technology isn’t always developed with diverse users in mind. But at Michigan Central, mobility innovators will design in the context of the area’s richly diverse neighborhoods, creating mobility solutions not just for some, but for all.

“We’re proud of everything that’s been accomplished since Ford announced our acquisition of Michigan Central Station in 2018,” says Mary Culler, president of the Ford Motor Company Fund. “All of our teams have done stellar work, especially in the face of a global pandemic. But we’re even more excited to see the Michigan Central innovation district come to life, bringing together members of the Detroit community and innovators from around the globe to create the mobility solutions of the future, for everyone.”