Newlab Research Shows Detroit Is An Ideal Hub For Innovation

September 16, 2021

What city has everything it takes to host a great leap forward in tech innovation?

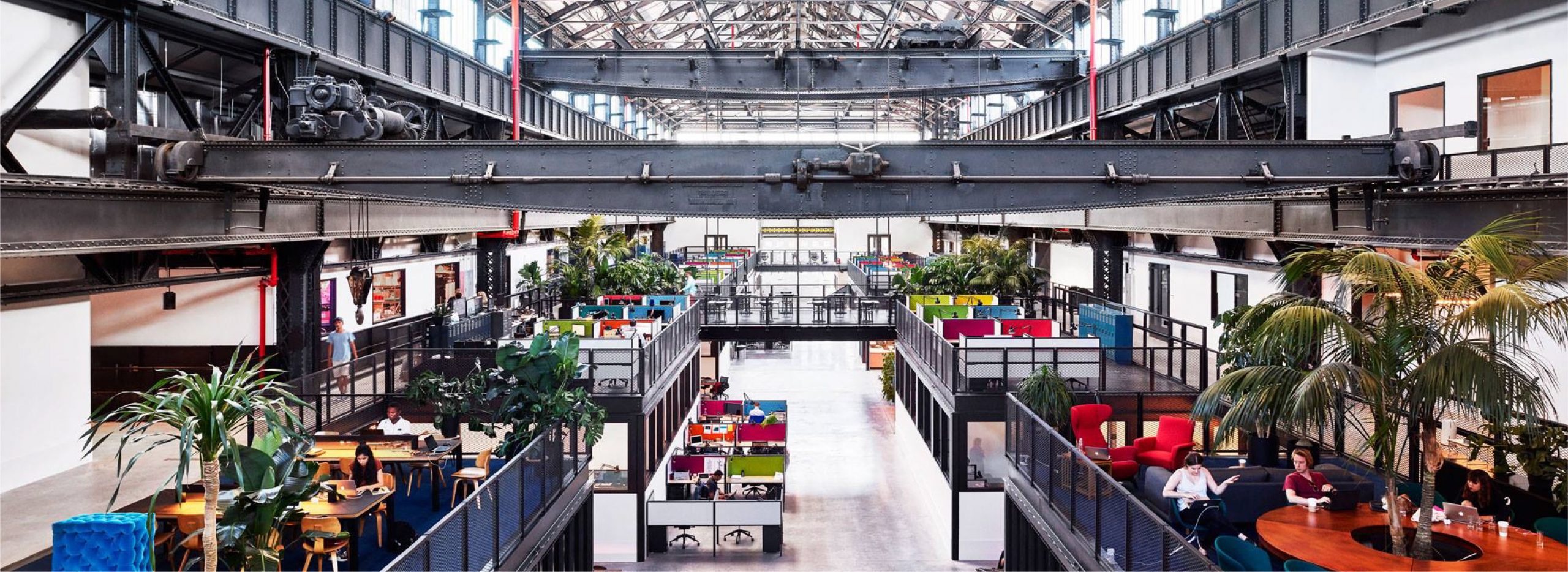

Newlab, a community of experts and innovators applying transformative technology to solve the world’s biggest challenges, is at the forefront of the technology and innovation ecosystem in New York City. It’s located in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, a mission-driven industrial park that is a nationally acclaimed model of the viability and positive impact of modern, urban industrial development.

And now, Newlab has its sights set on another major city with extraordinary potential to serve as a hub for transformative innovation: Detroit, where Newlab is currently working with Ford to help create an ambitious mobility innovation district anchored by Detroit’s iconic Michigan Central Station.

In 2015, Newlab’s founders, David Belt and Scott Cohen, faced an opportunity, and a challenge, very much like the one at Michigan Central today. The Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation had embarked on the process of transforming Brooklyn’s defunct Navy Yard. Like Michigan Central, the Navy Yard had been a vibrant part of the fabric and history of the city. At its peak, it employed tens of thousands of Brooklyn residents, was home to the first Navy hospital, and produced the battleships USS Missouri and Arizona. But for decades, the land had fallen into disuse.

So the mayor’s office asked for proposals that answered a simple question: what would you do with an extremely affordable 50-year lease on a giant abandoned shipbuilding facility?

The answer Newlab gave wasn’t the obvious one. They proposed to create a community where entrepreneurs, engineers and inventors could collaboratively innovate to address or solve urban problems. A place where they would have the best of everything they needed to innovate, and the support they needed, including connections with investors and fellow makers.

Belt and Cohen both had strong networks among tech entrepreneurs. But many of those entrepreneurs told them their idea for the Navy Yard would never work. At the time, New York City hadn’t been a significant force in manufacturing for years, and Silicon Valley was firmly established as the national center of tech innovation.

Newlab’s founders could see all kinds of innovation happening in New York City, from electric bikes being developed in a Midtown office, to a Harlem firm building exoskeletons to support “industrial athletes,” people whose jobs make a wide range of physical demands on them. But there wasn’t any center of gravity to bring all of New York’s tech innovators together, introduce founders to capital – and keep them from taking their tech to other cities that were already known as innovation hubs.

But Newlab won the proposal and raised $65 million to renovate the building, doubling its square footage with a second floor and adding event space, class and conference rooms, and a state-of-the-art prototyping system, including wood shops, metal shops, and 3D printing. Then they started inviting the most important ingredient: the innovators.

Newlab opened its doors with twenty-five companies. Today, it’s host to over 160 startups, and in the past five years has seen $1.4B in liquidity events for Newlab startups, including Uber’s acquisition of Jump bikes, which was pegged at over $200M, just 25 months after the company joined Newlab. And Newlab didn’t just meet its goal of keeping New York technologists in New York. It now welcomes innovators from around the globe: 38% of its current member companies are transplants from other cities.

Many of Newlab’s entrepreneurs move out because their operations grow too big to be hosted in the Newlab space. Some of them have moved to other parts of the Navy Yard, whose once-abandoned acres are now filled with restaurants, retail, and a new grocery store, and served by a new ferry service that connects the Navy Yard with Manhattan, only a few short minutes away. The Navy Yard employed 4000 people when Newlab opened its doors. Today, it employs 12,000. A new grocery store provides healthy, affordable food for residents of nearby public housing. And multiple modes of public transportation in the area have improved for local workers.

Newlab proved so successful in creating a vibrant ecosystem of innovation that requests for consults began to pour in as news got out. All kinds of people, from mayors to prime ministers, wanted to know if Newlab could build an innovation district for them, to bring their communities the benefits Newlab had brought to Brooklyn.

So Newlab built a model to analyze the elements of their success, and the best mix of conditions for future innovation districts. “What makes New York successful for us?” they asked. “And what city has those same ingredients?”

They wound up looking at a constellation of elements that, in their experience, had helped drive innovation. The first, says Newlab CEO Shaun Stewart, was academic institutions: “How much talent exists in the city and state? What are the fields of study? What are the areas of expertise?”

Next, they looked for a corporate infrastructure that rewarded young talent with the resources to go out and start their own ventures. The model also looked for supportive local government, willing to cut through red tape that can choke startups.

The final element: a strong existing ecosystem of innovation, because Newlab’s goal is to create a center that gathers existing innovators, not create something from nothing.

When all these factors are considered, across all the cities in the U.S., “Guess what comes out in the top three?” Stewart says. According to the Newlab model, Detroit is beautifully-positioned to thrive as an innovation district. It’s got major academic institutions like Wayne State and University of Detroit, which are part of a state-wide educational network that includes tens of thousands of students, at dozens of institutions of higher learning, including Michigan State, Grand Valley, and University of Michigan. Ford and GM are some of the largest and most innovative companies in the world, but Michigan is also home to Lear, Whirlpool, and many other companies with a history of innovation and key technical know-how in manufacturing at scale. Newlab also saw strong momentum in the existing ecosystem of innovation in Automation Alley and tech startups across the state.

At around the same time Newlab’s internal model revealed Detroit as a potential hotspot for innovation, Ford Motor Company had just acquired historic Michigan Central Station, with the goal of turning it into the anchor of a mobility innovation district. Ford’s vision for the station answered the central question Newlab asks when it considers working with a new city: “Why?” And because Ford’s team arrived for the meeting alongside a team from the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, Newlab could see from the start that government in the area supports innovation.

Since that initial meeting, Newlab and Ford have partnered on a pair of studios. The first, “Accessible Streets,” focuses on the needs of Detroiters living in the neighborhoods around Michigan Central. The second studio works on innovations on a global scale, to solve challenges in the future of global mobility, with a focus on electrification.

The Accessible Streets studio started in July 2020 by listening to Detroiters share about mobility in their everyday lives, as well as engaging local experts from the city, state, and nearby universities. Newlab identified key concerns for residents, including bridging gaps in current transportation systems, making streets safe and welcoming, improving information about existing mobility options, and better access to essential services like groceries, medical care, schools, and work. Then Newlab went to work recruiting startups from around the world with technology that might apply well to the needs of Detroiters.

This summer, the Accessible Streets studio announced its first cohort of startups aimed at meeting those needs. Today, those companies are working to bring local residents mobility information on solar-powered neighborhood displays, better access to essential resources through a robot delivery service, and solar-powered networks that improve WiFi, lighting, and security in Michigan Central neighborhoods. Blind and visually-impaired residents will also be offered a software application to aid their navigation of the city.

Newlab CEO Stewart looks forward to even more momentum in the future, as the restoration on Michigan Central Station is completed, and more innovators flock to the ecosystem of innovation. And from what he’s seen in Detroit, he says, Newlab’s assessment of Detroit’s incredible potential to serve as an ideal home for innovation is already proven.

“We’re seeing great success at Michigan Central,” he says. “Great collaboration, great partnership and progress. I’ve seen nothing but positive momentum, and positive signs.”